Who Gets to Build the Future?

And I can see another world

And I can make it with my hands

Who cares if no one understands?

I can see it now

I can see it growing

And moving by itself

And talking in its own way

It’s realer than the old one

— Stephan Merritt1

Dear circus artists,

We need to talk. Not about your circus practice, though – not here, not this way. It’s not that I don’t want to; honestly, I do! But there’s a snag, something special about today’s arrangement that keeps us from getting to the bottom of the matter.

Here’s the shape of it: from where I’m sitting, safe behind my computer screen, I just can’t know what you’re up to. Who are you, actually? I don’t know what circus is for you, what need it fills, what future lingers tantalisingly on its horizon. And I refuse to guess, out of respect for your particularity, and the particularity of your practice. I won’t do it, I won’t go there.

I admit, I’m guilty in the past of having jumped on the ‘what is circus’ train, proposing a universal definition, a specificity, an essence.2 I projected my own interests on you and made you the object of my knowledge without your consent or input.3 I thought I saw clearly, I thought I had access to the truest truth about circus. I’m sorry: now I see how presumptuous it was to try to confine your practice to the box which suited my own needs.

No, today I don’t feel the urge to talk about circus practice in a general way, nor the desire to perform the cut between circus and non-circus which would make such a discussion possible. It is not my decision (incision?) to make. Rather, I want to talk about circus as a community – the people of circus – and speculate about one possible future for us. This is it:

In the future, circus artists will feel empowered to create work on their own terms.

What do you think? It seems uncontroversial enough. I hereby declare it as my own mission and I propose to share it with you, if you want to be part of it. I hope you do, because it’s a future we need to work towards together: despite what your therapist might be telling you, we can’t conjure empowerment for ourselves out of sheer force of individual will, just by loving ourselves a little more or pushing a little harder. If creative agency is something that we value, we need to tend to circus as an ecology; that is, an enmeshed network of bodies, practices, institutions, images, moods, and concepts, which lean on, support, and transform each other in complex ways.4

Let me explain, starting with this word ‘agency’. It’s a word that we deserve to have in our arsenal. An agent being ‘one who acts’ (think agir, for all you French-speakers), agency is more or less ‘power-to-act’. When we think about our own agency as artists, the question we’re asking is: am I free to define the goals and values of my practice? Or am I forced to shape my practice in certain ‘normal’ ways in order to receive the material, emotional, and intellectual support necessary for making?

The opposite of agency is overdetermination. We say we are overdetermined when we don’t have as much freedom to choose how to act as we would like. Think about it this way: when we begin creating a circus piece, be it an act or a show, how much about it is determined in advance? What kinds of elements appear non-negotiable? Do I need to put in my best tricks? Do I need to keep the work to a certain length? Do I need to appear masculine or feminine? Do I need to avoid certain kinds of movements? To the extent that saying no is not an option – to the extent that our consent to these conditions is never asked for – we can say we are overdetermined, and our agency is compromised.

In 21st-century humans, overdetermination tends to create anxiety.5 When we feel we are not given a choice about our movements, when we feel held in our place by others and denied the power to decide for ourselves, we get sad, stressed, lonely, angry. Sometimes we don’t even know why we feel this way – sometimes overdetermination is so built in to our lifeworlds that the lack of choice doesn’t appear explicitly. But we can sense it, and it hurts.

I see a lot of circus artists in my community suffering the squeeze of overdetermination. For every circus artist whose career rolls on without a hitch, there are a handful whose work is not supported, not cared for, not allowed to take space. These are the artists whose practices fall on the wrong side of the split enacted between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ work. When this happens, we are overdetermined by critique: whatever system of evaluation happens to be in fashion that year swoops in to deny these artists the power to act.

This sort of overdetermination is very obvious to the artist. Less obvious – but no less discouraging – is the overdetermination effected by fantasy. How much do our cherished visions of ‘good circus’ actually limit our power to act in a given creative process? How much do mirages of a particular future cloud our access to the full potential of the present? When bodies, objects, images and language gather under the spell of a project, their gathering manifests an unruly, incoherent, swirling cloud of potentiality: on the way from the present to the future, anything could happen! When that cloud of potentiality appears to narrow, ushering us with all the force of violent destiny in one direction, agency is replaced by fate.6

Of course, we are never totally free to act. The only real question is: are we free enough, is our space of agency adequate? Well, is it?

In today’s circus world, critique and fantasy are entangled with each other in an elaborate and messy fashion. Critique punctures fantasy: it derails careers, deflates practices, disables creativity, and detaches the spectator from the situation of the performance.7 At the same time, critique constructs fantasy: the critical environment we’re immersed in feeds us values and tells us what good and bad performances look like. Critical culture encourages us to fantasise about ourselves as critics – when criticising others, we help build a hierarchy of taste, with ourselves sitting at the top, as if we and we alone had access to the truest truth.8 The circus world, diffracted through the binocular prisms of critique and fantasy, appears as an arena of struggle – taste against vulgarity, artistry against clumsy flailing, authenticity against artifice – rather than as a delicate ecology requiring common tending.

This state of affairs is held in place by a secret. If the secret were to be spoken, the whole drama would be revealed as hollow. And I’m going to speak it here, so get ready! Here is it:

There is no objective ‘good’ or ‘bad’ in performance, only personal taste and local criteria.

I’ll repeat: in performance, the only basis we have for making judgments of value are personal taste and local criteria. Anything we might want from a performance – entertainment, social commentary, political import, impeccable design, clever decision-making, originality, style, whatever – none of these things are universal values for performance, nor do they look the same in different places around the world (or even for different people in the same place).

It becomes pretty clear if we examine the different places circus is presented. The criteria which hold at a nightclub in London look pretty different from the criteria which hold at a street arts festival in Spain. ‘Good’ and ‘bad’ mean different things at CIRCa festival than they do at Adelaide Fringe. This is obviously not because different geographies grant us fuzzier or clearer access to the Truest Truth: in each location, we are bound by a local resolution, whose reality is performatively maintained.9 We have to keep judging – and judging our way – in order for ‘good’ and ‘bad’ to appear at all.

These local critical criteria sometimes become a problem for artistic agency. In the commercial world, artists make work for the pleasure of a particular audience, and manage to find space for creative freedom within the confines of those criteria. Commercial artists agree to abide by the demand for entertainment – they consent to work within the constraints drawn by the critical culture local to the commercial world. When submission occurs with consent, the results can, of course, be rewarding for everyone.10

Things are different for circus practices which understand themselves as art. That’s because in contemporary art, the audience doesn’t need to be entertained – not necessarily. In fact, the artist gets to define her own ends: she becomes her own local resolution of reality.11 The circus practices which we call ‘contemporary’ can be informative, emotional, exciting, meditative, confrontational, confusing – or not. This is the space of agency promised by the contract of the contemporary. And increasingly, I’m concerned that that promise is not being kept.

Despite loudly claiming that rules are meant to be broken and that all conventions are arbitrary, we continue to critique artists as if our local criteria and personal taste were as real to them as they are to us.12 We continue to enact the division between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ work which keeps some practices visible and some in the shadows. And when we voice our criticisms in certain ways – ways which erase the particularity of our criteria of judgement – artists get trapped in certain ways of thinking, overdetermined by fantasies they feel they cannot ignore or negotiate.

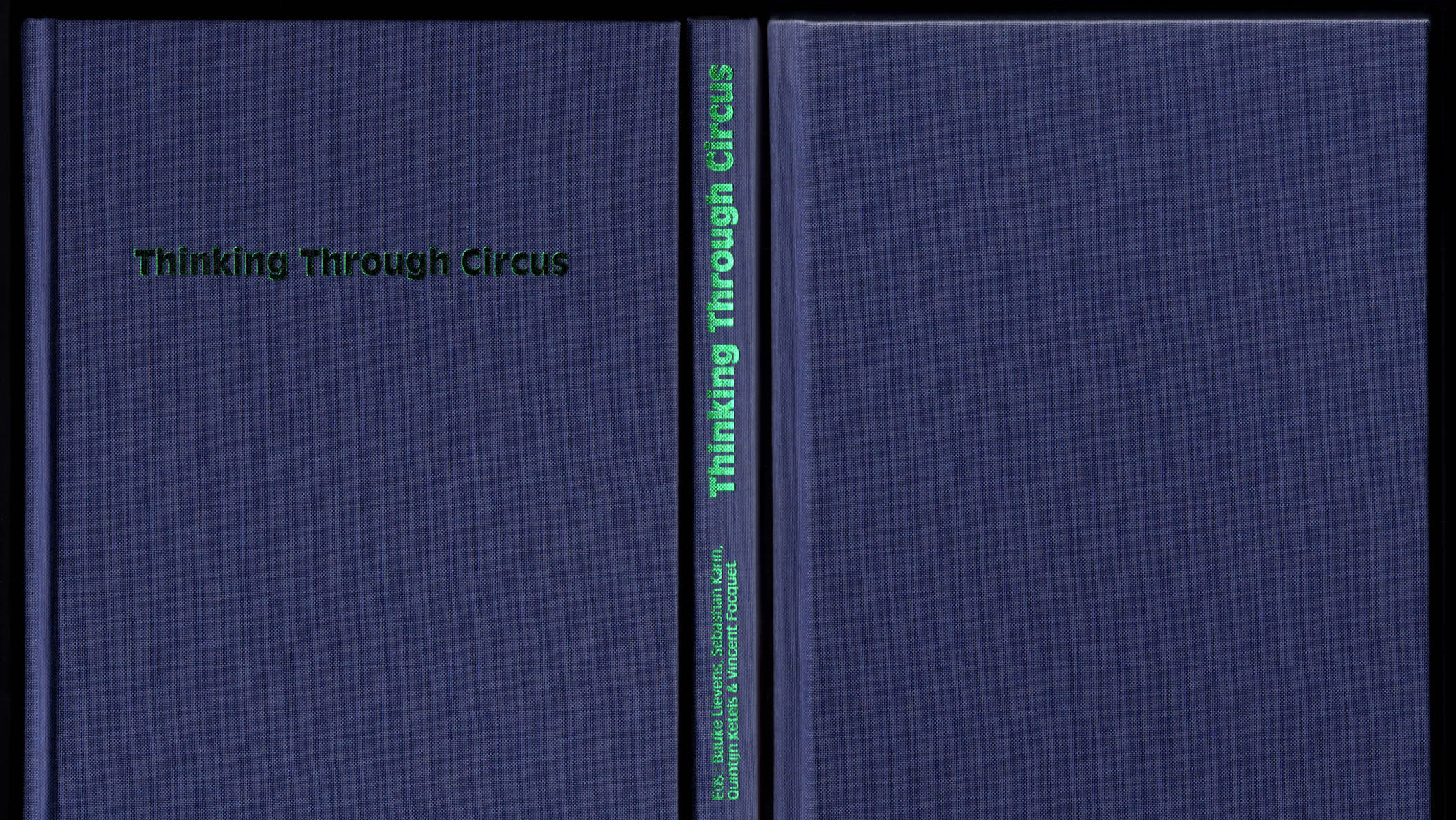

In Bauke Lievens’ first open letter – ‘The need to redefine’ – critique and fantasy intersect in yet another arrangement. In my reading, the whole letter is grounded by a fantasy of critical circus. Lievens imagines the circus artist as a kind of skilled cultural operator, whose practice is based on the virtuosic navigation of conventions – both artistic and social – and their critical deconstruction through performance.13

What does this mean? Well on the one hand, Lievens wants the artist to take a hard look at circus as a medium, to pull back the curtain of misunderstanding and reveal its reality. In her letter she states:

The circus body constantly pushes the limits of the possible, and incessantly displaces the goals of its physical actions, such that it never attains these goals and limits: they are always moving to be just out of reach. What is expressed through the forms of circus is not the old vision of mastery, then, but an understanding of human action that is fundamentally tragic [….] What appears in the ring is a battle with an invisible adversary (the different forces of nature), in which the goal is not to win but to resist and not to lose.

So critical circus reveals something essential about the medium which had been hidden. On the other hand, critical circus offers up a critique of contemporary culture (‘our post-modern, meta-modern or even post-human experiences of the world surrounding us’). The artist’s task, then, is to propose, through performance, an ‘innovative, surprising, weird and disturbing’ relation between medium and world.

There’s no denying that the figures of thought Lievens develops have a palpable force of presence: her concept of the tragic circus hero, for example, radiates a compelling productive energy. This energy has already been and will continue to be mobilising for circus artists. But I think we need to be clear that her writing is so rich precisely because it is particular to her embodied experience: she’s expressing her truth, which has emerged through her own particular circus practice.14 There’s a particular vision of circus behind her writing, one which deals with risk, danger, and difficult physical skills. There’s a particular world – one which is, strangely enough, both meta-modern / post-human and characterised by a dialectical struggle between Man and Nature.15 Lievens also imagines a very particular task for art: to stir up the social and aesthetic fields, to take the flaming sword of critique to each, to make hidden truths public, and to motivate public engagement with them through persuasive staging.16

This is totally one valid way of thinking about arts practice. Is it the only one? No. When I think about Lievens’ approach in relation to my own practice, what I notice is that one very important element of my work – the intuitive body – is missing from her account. Because Lievens’ circus seems to be all about making clever jabs at social and aesthetic conventions, the body of rational planning seems to be very much in charge.17 Sometimes, though, I’m more curious about feeling than reasoning; sometimes I’m more interested in a state than a statement. Sometimes, material emerges during creation which is romantic, which is autobiographical, which is unreadable. Sometimes I make decisions without knowing why – not always, but sometimes.

In her letters, Lievens gives us a peek of the kind of things that she desires. But what I notice is that, rather than offering those fantasies to us – saying ‘hey, I’ve got this crazy idea, maybe we can share it, maybe you vibe with part of it, go wild guys’ – she presents them as non-negotiable. She sows a seed of division in the circus world – are you Team Bauke? – and, as added incentive to get on board with her vision, insists that other ways of thinking about circus are old-fashioned, backwards, or stuck in the past.18 She constructs a normative timeline for the development of circus without asking other artists if they want to join her in her charge. But is there only one circus future worth pursuing? Is there only one contemporary?19

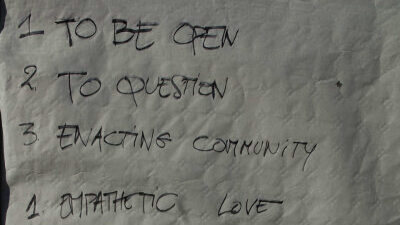

I want to speculate about the practical conditions of a future in which circus artists feel empowered to create work on their own terms. I think this begins with a culture of respect: when you read a dossier, feedback a work-in-progress, or see a show, assume the artist knows what she’s doing. This should be a sort of baseline principle. When something doesn’t seem right and you want to point it out, first ask the artist questions: is coherence important for you? Is it essential to your practice that the audience remain engaged the whole time? Are you interested in clarity? Do you think circus needs to be difficult? If the answer is ‘no’, maybe your critique is more about your fantasies than theirs.20

I think the biggest threat to circus artists today is critique that refuses to relativise its grounding fantasies. In a contemporary circus context, nothing should be absolutely required of a circus show. But all too often, artists end up juggling demands which appear both non-negotiable and incompatible with their practice. For me it all started in circus school: in today’s schools all work is graded according to the same criteria, and critical culture tends to run rampant. At school, we internalise overdetermining fantasies about ‘good circus’ which then take years to unlearn. What if teachers were asked to work with their students to write evaluation criteria tailored to their actual interests? What if circus schools made a habit of articulating and problematising their own aesthetic values?

Although the grading stops after school, evaluation – mostly oral, although sometimes also written – does not. Occasionally these critiques make it back to the criticised artist, but more often they just infect the defenseless listener with an imposed set of values. If we don’t criticise carefully, we end up forcing our fantasies on others in ways we might not even be aware of: if I hear ‘too bad they didn’t fully explore the scenography’ enough times, it’s hard not to start thinking of scenography as something which must be ‘fully explored’. So if we’re serious about circus as a place where artists can choose to shape their practices in multiple ways, we might need to take a look at our habits of speech. We might need to think about how our criticism is quietly building norms which hem artists into particular kinds of fantasies – fantasies which they might struggle to accord with their creative practices.

Being careful about the way we think about and communicate critique doesn’t mean an end of analysis and debate. Far from it! It just means deploying analysis as one possible tool for performance-making, rather than understanding performance as an excuse to do analysis. It means ‘destabilising’ our standpoints, so that when we use language to come into relation to someone else’s practice, it’s not only they who are vulnerable, but also us.21 We have to allow the work the space to speak back, and that involves signposting the particularity of our own speaking positions, instead of presenting ourselves as all-knowing keepers of universal truths.22 Until we’re ready to do this, it’s maybe better to remain quiet, rather than assume we know better than the artist what her practice requires.23

The circus field is populated by a diverse crowd, with a plurality of artistic practices. Some of us begin creation thinking in terms of story, some in terms of images, some in terms of physical tasks. Some of us are addicted to language and some feel trapped by it; some of us are inspired by the ‘real world’, and some need to shut that studio door tight in order to feel comfortable exploring. Sure, some circus artists romanticise a kind of off-the-grid, chapiteau-and-caravan existence, but many of us are also expert digital citizens, even using the internet as a kind of alternative performance space. Rather than trying to correct ‘undesirable’ tendencies by pointing to what circus should be according to one particular understanding of the here-and-now, we need to nurture and cultivate precisely this diversity. Otherwise, we privilege one approach – and one local set of evaluative criteria – over another, adding more arbitrary stratification to a planet already bursting at the seams with it.

It is especially important in contemporary circus that we stop undermining each other with insensitive critique. Taking each other seriously as artists means first asking the question: what would it mean to understand my experience watching this piece as a valuable experience? What if the artist is not incompetent, but actually doing something strange totally perfectly?24 Unless there’s an ethical problem with someone’s practice – if it’s promoting sexist stereotypes, for example, or if the work is physically or emotionally damaging for the artists involved – everything and anything must be received in a spirit of unconditional hospitality.25 Otherwise, contemporary circus loses its political potential as a space of freedom, simply becoming another normatively defined aesthetic or style.26

If there’s an issue with circus, it’s not that the work is lacking some magic ingredient. Perhaps there’s a certain conservatism that frustrates artists trying to think differently about their practices. But proposing a ‘better normal’ is not the answer to the problem. We can’t think about progress only in terms of our own aesthetics and values systems; we need to consider the field as a holistic ecology, shaped by artistic practices but also by social, administrative and epistemological ones. The goal should not be better shows but greater artistic freedom. And in these spaces of creative agency, artists – not critics – will find themselves empowered to define a plurality of circus futures.

Let’s do it together.

Works Cited

Arendt, Hannah. 1960. ‘What is Freedom?’ In The Portable Hannah Arendt, ed. P. Baehr, 2000. 438-461. New York: Penguin.

Avanessian, Armen. 2017. OVERWRITE: Ethics of Knowledge – Poetics of Existence. Trans. N. F. Schott. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

Bal, Mieke. 1999. ‘Narrative inside out: Louise Bourgeois’ Spider as Theoretical Object’. In Oxford Art Journal, vol. 22, no. 2, 103-126.

Barad, Karen. 2003. ‘Posthuman Performativity: Toward an Understanding of How Matter Comes to Matter’. In Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, vol. 28, no. 3, 801- 831.

Bhabha, Homi K. ‘“Race” Time and the Revision of Modernity’. In Theories of Race and Racism: A Reader. Ed. L. Back and J. Solomos, 354-368. London and New York: Routledge.

Butler, Judith. 2015. Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly. London and Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Dhawan, Nikita. 2014. ‘Affimative Sabotage of the Master’s Tools: The Paradox of Postcolonial Enlightenment’. In Decolonizing enlightenment : transnational justice, human rights and democracy in a postcolonial world, 19-79. Ed. N. Dhawan. Leverkusen, Germany: Barbara Budrich Publishers.

Derrida, Jacques. 2000. Of Hospitality. Trans. R. Bowlby. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Fanon, Frantz. 2008 [1967]. Black Skin, White Masks. Trans. C. L. Markmann. London: Pluto Press.

Glissant, Édouard. 2010 [1997]. Poetics of Relation. Trans. B. Wing. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Goldberg, RoseLee. 2014 [1979]. Performance Art: From Futurism to the Present. London: Thames & Hudson.

Kunst, Bojana. 2015. Artist at Work: Proximity of Art and Capitalism. Winchester, UK and Washington, USA: Zero Books.

Latour, Bruno. 2010. ‘An Attempt at a “Compositionist Manifesto”’. In New Literary History, 2010, 41, 471-490.

Massumi, Brian. 1992. A user’s guide to Capitalism and Schizophrenia: Deviations from Deleuze and Guattari. London and Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Puig de la Bellacasa, Maria. 2017. Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More than Human Worlds. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press.

Verwoert, Jan. 2013. ‘Criticism Hurts’ and ‘Why Is Art Met With Disbelief: It’s Too Much Like Magic’. In Cookie!, 29-43 and 91-106. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

—. 2016. ‘How would I know how to say what I do?’. In No new kind of duck. Ed. J. Verwoert, 13-36. Zurich and Berlin: Diaphenes.

Notes

1 ‘’71 I think I’ll Make Another World’, from 50 Song Memoir by the Magnetic Fields (2017).

2 See ‘Taking back the technical: contemporary circus dramaturgy beyond the logic of mimesis’ (Kann 2016, online).

3 If I claim to know what you are, do I not also cut away all the parts of you which are not visible from my limited perspective? And if I’m the one who has the power to define common knowledge – if I’m the one whose writing is being published, for instance – what happens to the elements of your being which I cannot know or sense? In Poetics of Relation, Édouard Glissant urges us to drop the Western fantasy of objective knowledge – of ‘discovering what lies at the bottom of natures’ (2010 [1997], 190). Rather, Glissant suggests we turn our attention to the ‘texture of the weave and not the nature of its components’ (190). Instead of making claims for others about what they are – claims which perform violent reductions – we might be better off examining the nature of the contact we manage to establish. To ground an ethical practice of knowledge, we need to stop asking ‘who or what is this?’, wondering rather ‘what does it feel like to come into relation with this person or object?’.

4 Why is it so counter-intuitive today to think of agency in terms of ecologies? Judith Butler, among others, has pointed out the way neoliberalism wages ‘war on the idea of interdependency’ (2015, 67), shifting all responsibility to the individual. In neoliberal climates, we tend to think of agency as something that belongs to the agent, rather than as something granted to the agent. But, as Butler argues, ‘Human action depends on all sort of supports – it is always supported action’ (72; emphasis mine). We have only to think of the circus apparatus to understand what she means. Climbing is unthinkable without a rope. In the same way, touring would not look the same without networks of cultural institutions, training is shaped by the networks of sociality that grow in the training space, and artistic practices develop in ways that are inseparable from the ebb and flow of critical recognition.

5 How does it feel to know that your horizon of possibility is defined in advance by others – and by others for whom your position is more a curiosity than a real concern? For a gripping account of the embodied effects of overdetermination, here in reference to race, see ‘The Fact of Blackness’ in Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks. In Fanon, whiteness appears as a kind of unbearable and inescapable constraint, a ubiquitous condition which closes the space of black agency: ‘All round me the white man, above the sky tears at its navel, the earth rasps under my feet, and there is a white song, a white song. All this whiteness burns me [….] All I wanted was to be a man among other men. I wanted to come lithe and young into a world that was ours and to help to build it together [….] and then I found that I was an object in the midst of other objects’ (2008 [1967], 82-86).

6 For radical performance theorist Bojana Kunst, the fantasy of the ‘good performance’ poses a major threat to artistic practice. The strict control we need to exercise in the creation space in order to move towards a certain desirable outcome means there is actually no space to produce anything new: ‘frozen in the future’, we keep on circling around what is already imaginable, continually reproducing new versions of the same (2015, 153). For Kunst, this means that the potential of art as a space of freedom – as a space in which bodies can move in defiance of the rules which bind society at large – is barred: when we hold on too tight to fantasies of critical excellence, ‘the possibility of the future is actually in balance with the current power relations’ (168). Avoiding overdetermination by fantasy perhaps means operating with a looser grip…

Since Freud’s discovery of the subconscious, it has become very hard to argue that there’s any real freedom in fantasy. I fantasise about futures despite myself. And as Hannah Arendt points out, ‘The power to command, to dictate action, is not a matter of freedom but a question of strength and weakness’ (1960, 445). Agency – at least in the way I’m interested in understanding it here – is not about being able to actualise what we already imagine is good. Rather, it appears when we are able to transcend ‘motives and aims’, calling something into being ‘which did not exist before, which was not given, not even as an object of cognition or imagination, and which therefore, strictly speaking, could not be known’ (444). In terms of artistic creation, this means treating the image of ‘good performance’ as a material which is present in the space of creation like any other material, appearing as a possible interlocutor rather than a totalising ideal.

7 In the sense that critique requires analytical distance. When we sit in the audience with our critic’s notebook on our lap, the experience of spectatorship acquires quite a different flavour.

8 The critical gesture is one of revelation: it is ‘predicated on the discovery of a true world of realities lying behind the veil of appearances’ (Latour 2010, 474-475). By making this gesture, the critic claims ‘a privileged access to the world of reality’ (475). Critique only functions if the critic stages herself as more-objective, and her critical criteria as unassailable. This is what commentators like Armen Avanessian mean when they frame critique as an instrument of power: it has a stabilising and legitimising effect for the critical subject (Avenessian 2017, 35-36).

9 I borrow this formulation – and the metaphysical worldview grounding this letter – from philosopher Karen Barad. In ‘Posthuman Performativity: Toward an Understanding of How Matter Comes to Matter’, she unfolds a performative approach to the production of realities, which imagines all being as local, contingent, and relational: ‘A specific intra-action […] enacts an agential cut […] effecting a separation between “subject” and “object”. That is, the agential cut enacts a local resolution within the phenomenon of the inherent ontological indeterminacy. In other words, relata do not pre-exist relations; rather, relata-within-phenomena emerge through specific intra-actions’ (2003, 815).

10 I think problems of agency mostly arise in the commercial world when artists are asked either to overtly sexualise themselves or to take more significant physical risks than they are comfortable with. These are problems of no small import, and deserve to be treated in a study of a different kind.

11 Which is not to say that her local resolution goes unchallenged. In ‘Why Is Art Met With Disbelief? It’s Too Much Like Magic’, art critic Jan Verwoert describes the tension wrought on the artist by the constant demand to explain herself: ‘It’s a classic among the top twenty conversations from hell: getting cross-examined over Sunday dinner by prospective in-laws who, with increasing persistence, try to elicit a confession from you that […] art is a big fraud [….] In such a situation, defending art as a realm in which value can be freely negotiated seems hardly worth trying’ (2013, 92; emphasis mine). Should we as artists echo this assault on artistic freedom through holding each other to inflexible critical standards? Or should we devote ourselves to ensuring that art remains a space in which value can be freely negotiated?

12 For a positively encyclopedic account of performance as a practice of convention-breaking, see RoseLee Goldberg’s Performance Art: From Futurism to the Present (2014 [1979]).

13 I owe this formulation to Jan Verwoert (2016).

14 Lievens is not trained in a particular circus discipline, but she is a circus artist in the sense that she composes with circus, interacts with circus, deals with circus, feels with circus. In other words, she is a circus artist because she has a circus practice; she’s both immersed in it and speaking back to the world through it. If we are to claim, as I would like to, that making circus technique is a kind of thinking, equal in worth to thinking-through-speaking or thinking-through- writing, then we can’t be snooty about including dramaturgs, directors, and choreographers-of- circus from circus proper. We are all circus artists.

15 Strange because post-human thought is characterised by the deconstruction of the division between the natural and the cultural, and is animated by the imperative to think in terms of ecologies rather than dialectical oppositions. Post-humanism tries to undo what Lord Alfred North Whitehead called the ‘bifurcation of nature’, which names the attempt to separate meaning from matter spearheaded by European Enlightenment thought. Rather, posthumanism tries to ‘speak in one breath of nonhumans and other than humans such as things, objects, other animals, living beings, organisms, physical forces, spiritual entities, and humans. Encompassing this ontological scope is vital as it has become indisputable, if it ever wasn’t, that in times binding technosciences with naturecultures, the livelihoods and fates of so many kinds and entities on this planet are unavoidably entangled’ (Puig de la Bellacasa 2017, 1). With this in mind, a post-human tragic hero at war with nature is difficult to imagine.

16 The fact that this prescription hides within her text as an implication makes it all the more dangerous for artistic agency. It’s the belief we have to adopt, at least temporarily, in order to make sense of Lievens’ critique. In the act of reading, we don’t only encounter information; we also immerse ourselves in a whole context which allows the information to resonate as truth.

This is what Deleuze and Guattari call a mot d’ordre: it’s what goes without saying in what is said. Such rhetorical strategies are the building blocks of ideology. Unless we’re explicit about the fantasies which ground our critiques, we end up indoctrinating readers rather than liberating them to think for themselves (Massumi 1992, 29-34).

17 The culture of critique finds its roots in the European Enlightenment: thinkers of this period challenged the old orders of Church and State by the use of reason and persuasive argumentation. In the process, they denigrated and marginalised ‘affect, the subjective, the particular, the familial’… in the quest for objective knowledge, Enlightenment thought attempted ‘to divorce reason and cognition from experience, intuition, and affect’ (Dhawan 2014, 23-29). What resulted was a hierarchisation of thought, with Western models of objective criticality at the top. Taking embodied practices seriously as valid ways of doing thinking means putting this hierarchy into question.

18 If we continue to talk about ourselves like this, we put ourselves in a very difficult position! It’s only possible to imagine that we are somehow behind, late, or caught in the past if we believe in history as a single, inevitable process of progress; a universal movement towards one kind of future. But who gets to decide what this future is? And what becomes of diversity when the nature of progress is dictated from only one standpoint?

19 Rather than simply adding practices coded as ‘old-fashioned’ or ‘primitive’ into a revised version of the present – forming a ‘new totality’ – Homi K. Bhabha suggests the space of difference opened up by ‘time-lag’ (that is, the perception of certain practices as old-fashioned) as heralding an opportunity for the inauguration of a horizontal plurality of presents (2000).

20 Jan Verwoert on critique: ‘We all have the required amount of kitchen psychology at our command to figure out the reasons why [a] person must have uttered the hurtful judgment. It’s the golden rule of criticism: Critics reveal as much, if not more about themselves (their fixations, complexes, and grudges) as they do about the object of their judgment’ (2013, 32).

21 In OVERWRITE, literary theorist Armen Avenessian puts forth a theory of the ethics of critique. For him, critique is merely activity of self-legitimation unless the act of criticising also transforms the critic: ‘The search for a path that leads beyond or emancipates from the status quo always also implies a poetic labor on oneself. In the absence of such labor, changes are just cosmetic changes’ (2017, 40-41). In other words, unless the critic is willing to be changed by the process of criticism – unless she’s willing to revise her grounding fantasies – criticism actually produces no real effect in terms of the dominant culture.

22 Thinking along with Mieke Bal, I’m proposing circus performance as a theoretical object. In Bal’s conception, a theoretical object is not an object to theorise, but an object that theorises itself: ‘the term refers to works of art that deploy their own artistic […] medium to offer and articulate thought about art’ (1999, 104). Her formulation reminds us to think of the critical instance not as the bestowal of words upon a mute object, but rather the awkward and tentative meeting of two ‘speaking’ subjects, who together negotiate the production of knowledge.

23 Verwoert describes the ‘articulate silences’ of the critic who decides not to speak as ‘forms of mourning’. Mourning for what? Perhaps these moments of silence commemorate the failure of her attempt to make contact, the tragedy of non-relation that undergirds our irreducible difference (2013, 43).

24 I think a key concept here would be temporary belief. If we want to engage in a generous practice of dialogue, we need to make the effort to imagine that the other’s point of view is valid – we need to experiment with adopting their critical criteria, if only temporarily. This goes for the artist receiving feedback just as much as the critic who gives it. Without making this effort of empathy – without adopting temporary beliefs – our critical positions would never transform or change. I owe the concept of ‘temporary belief’ to Eleanor Bauer, who introduced it in a workshop as a way to think about the dancer’s relationship to a choreographic score.

25 For French philosopher Jacques Derrida, the host is always torn between two forces. On the one hand, we have the ethical or moral principle of hospitality, which obliges us to provide space for anyone who needs, without judgement or expectation of repayment. On the other hand, we have the conditions and laws governing hosting as a practice – think of immigration law, for example – which translates the unbearable burden of caring for everyone who needs into practical terms. Because we don’t have large enough houses to take in everyone, nor the social or emotional resources be a good host for just anyone, we make selections, perform exclusions, subject prospective guests to a series of measurements and evaluations, either consciously or subconsciously.

By making this distinction – between the principle of unconditional hospitality and the practice of conditional hospitality – Derrida wants to point at a space of injustice. What to say to those who fall into the gap between doing the right thing and doing what you can? No one deserves to be excluded, yet total inclusion – in the arts as much as anywhere else – remains a logistical impossibility. Derrida concluded that the vain quest for total inclusion needs to remain a mobilising force, even if the work of inclusion is never complete (2000).

26 André Lepecki’s distinction between the choreopoliced and the choreopolitical is helpful here. If contemporary circus becomes a set style rather than an open-ended invitation to redefine itself, we fall into a situation of choreopolicing: that is, a field in which ‘to be is to fit a prechoreographed pattern of circulation, corporeality, and belonging’ (2013, 20). If this happen, artistic freedom in circus risks vanishing. On the other hand, a choreopolitical field is one which welcomes ‘movement whose only sense (meaning and direction) is the experimental exercise of freedom’ (20); movement of which, in other words, no particular performativity is required, and which doesn’t need to wait for critical legitimation.

Hello, World!