Farewell: Reading Knots

1. READING KNOTS

Dear reader

Since 2020, we have been collaborating on a rigging practice in the framework of the artistic research project The Circus Dialogues (continued) at KASK School of Arts in Ghent, Belgium. The practice has assumed many forms. We called it a collective rigging practice, a speculative rigging practice, we called it a preparatory practice, we called it rigged dialogues, in-between sessions We have been tying, writing, moving, suspending, reading… And talking, we’ve done

lots of talking. Looking back at it, you could say that in all these diverse ways we have tied knots. The knots consisted variously of ropes, words and affects. Some knots were simple and practical. Some didn’t hold. Others were complicated and impossible to undo.

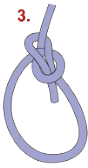

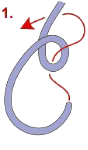

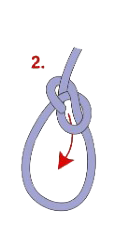

A bowline

A butterfly knot

An eight

A double eight

A fist knot

A Spanish bowline

A fisherman’s knot

A basic Shibari knot

A clove hitch

A double fisherman’s

A Prusik knot

A reef knot

A sheet bend

A double column knot

Rigging in circus, we temporarily defined, is the practice of tying things together so that they can hold (others). It is a preparation for things and practices to come. Rigging is about making things possible, about making things safe. It requires the knowledge of what can hold what. How to keep these straps or this trapeze and their artist in the air? What kind of connections (carabiners, knots, slings…) are necessary for the structure to carry, to persist and invite for movement? Importantly, it also requires negotiation and planning. What forces are at stake here? And what will we need to continue?

The starting point of the project was the desire to make rigging visible. A circus performance, the part of circus practices that most audiences get to see, typically starts after rigging and ends before de-rigging. In a broader societal context that similarly obscures structures and labor of care and support, we wanted to focus on the part before the performance: on rigging. What if we turn the lights on earlier? What if we stop after rigging?

In six letters I will say goodbye to the rigging project and pass it on by re-formulating it both for myself and for you.

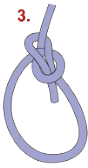

During one of the first days in residency, rigger and co- researcher Saar Rombout, explained us to always ‘read’ a knot after you made it. Reading a knot means re- tracing the trajectory of the ropes to check if they grip each-other the right way and to undo possible twists and irregularities. Similarly, I will try to read the knots we made in the past year, while talking, attaching, writing, moving, and reading. I will look for the twists but leave them as they are. You can read along.

I’ll write nine more letters, each following its own, sometimes confusing, logics, intersecting writings generated during the past years with other texts, current thoughts and (internet) images. Using this practice of expanded letter-writing we’ve been developing together within the project, I hope to create an opening that allows for these thoughts to persist, to continue, in a multitude of forms, practices and people.

Throughout the letters, you might notice a preoccupation with (queer) temporalities, intersecting past, present and future. That’s what, underneath it all, we were busy with, I guess. You’ll notice that for each letter and within the letters themselves, the address switches from one to another. From you, the reader, to the thing I’m talking about, back to others and back to you.

All my warmth,

Vincent

2. LOOKING BACK FROM HERE

Dear future,

I want to address the second letter of this series to you. I feel you peaking over my shoulder when writing this letter on a rather sunny spring day at a wooden kitchen table somewhere in Brussels. You’re so very present in this situation, just like you were in the rigging practice. We were constantly trying to bring and dream about better futures, more sustainable ones. I think we fetishized you. Now that I think of it, maybe I’m doing it again just now, by addressing you like a singular entity. Let’s start again.

Dear futures,

This is a letter for all of you. I’m wondering what you might be. We were so busy creating the possibilities for you to arrive, but it’s hard to feel you are out there. Like you exist autonomously somewhere outside of the now, outside of the people working to dream you together. Like you’re waiting around for the now to be over and replace it. That doesn’t feel entirely right. Maybe I should try again and start this letter one more time, from the address.

Dear imagined and hard to imagine futures, constantly coming about,

That’s as close as I will get to describing you. It took me more than 200 words to even get to this point, so might as well get to it and start with saying what I want us to chat about. Dear imagined and hard to imagine futures, constantly coming about, I want to have a talk about the past.

During residencies, meetings and in letters all too similar to this one, you’ve been something we as a research team talked, dreamed, worried and exchanged about. From the very first residency, we’ve defined speculation as a method. Building on the work of Belgian philosopher Isabelle Stengers in amongst others Cosmopolitics I (2010), we understood speculation as

Learning to resist a future that presents itself as obvious, plausible and normal … To resist a likely future in the present is to gamble that the present still provides substance for resistance, that it is populated by practices that remain vital even if none of them has escaped the generalized parasitism that implicates them all. (10)

Using strategies as ‘making important’ and ‘creating fertile soil for the possible’ we’ve conceptualized our rigging practice as a preparation for the future. Preparation and rigging, we felt, were closely related. What else is rigging than preparing for a future you wish to come? That future could be a performance, a training session…

You were so central to our conversations that, now the rigging project ends, I feel a suspicion for you. Maybe that’s why I don’t want to talk about you in this letter, dear futures. You keep overwhelming my mind, while it’s the past I want to address with you. And, before you start thinking otherwise, I’m down with all the non-linearity and the false dichotomies between past and present and present and you and you and past, but you’re also very much here as a concept, and you bring about the past as a concept too, so let’s talk about it. In the past I was an artistic researcher very concerned with creating fertile ground for different futures. I think in a way, I had been hoping that the futures would become tangible in the timeframe of the project: before 2024. That’s a very fucking tight schedule for a sustainable future.

I’m reminded of a passage from the book I’m currently reading. In The Seep by Chana Porter (2020), an extraterrestrial entity, calling itself ‘the Seep’ enters earth, rendering everyone deeply and viscerally connected. Capitalism falls and the concept of linear time ceases to exist. In the book, the Seep communicates with inhabitants of earth via an immaterial digital pamphlet that spontaneously appears. On page 110, this is what the pamphlet has to say about the idea of linear time in a message to the main character who is currently dealing with the fact that her life partner has chosen to re-become a child:

Here’s our idea, Trina, about why humans are so focused on the past and the future, all at once. it’s about learning! that’s the great gift of linear time! you can look back on your experiences in the past and use them to make choices for the future. Time is embodied learning! That’s why memory exists! Why failures are never truly failures, and mistakes are always glorious! No matter what, no matter what, no matter what, no matter what!’

That resonates with me in the strangest of ways and I hope it does with you too. I wonder how you are relating to the past? You must know, dear futures, our project was all about undoing norms. The dominant Western construct of linear time was one of them. But if, like The Seep seems to describe, the benefit of linear time, of the idea of looking back at a past, is learning. What is it we learned? Sticking to the linear timeline. This letter is written from the future, looking back at the past of the rigging project. What would this future feel like from the past of the project? Reconsidering this past of hoping for better futures and working for them to come about, I must think of exhaustion. That’s a concept I will try to elaborate on in the next letter.

I’ll see you around somewhere future, or not, or (probably) differently Looking forward and backward and all around

Vincent

3. NO MORE

Dear endings,

The name of the research project is The Circus Dialogues (continued). ‘Continued’ refers to the fact that the project is a continuation of the previous research project The Circus Dialogues (2018-2020). But the idea of continuing is way more important than that. “How to continue?” was a question lingering throughout every action of the project. It was a reaction to the exhaustion we were feeling in the field, our broader environments and increasingly in our personal lives. Looking for sustainable practices, we set off this journey wanting to find ways to continue. How to fit this end into this narrative? Should we simply recognize the failure to bring about a sustainable future? Or is there something to say for ending as continuing? Or ending to continue? And finally, when does ending end?

During our residencies, we had diverse writing practices in which we wrote Tarot cards

or letters or practiced automatic writing. I remember the many times in which endings

came up as a subject in these writings. We talked about death, about exhaustion, about

quitting. I can’t pinpoint where this obsession came from. Maybe it was a desire for

stopping things that were dragging us down (including, often, the project itself). But

maybe, and this is a brighter thought, for other futures to come, some things need to end.

I think my favorite endings are refusals. Refusing to

continue. Refusing the status quo. During the process I’ve grown

increasingly fascinated with people who quit what they are doing,

because it’s harmful, because it gets too much, because it’s just

not what they thought it would be. There was something in this

refusal of normative, evident, futures.

There is a film by Charlie Kaufman called I’m Thinking of Ending Things (2020). It’s an adaptation of an Ian Reid novel. In the opening scene: the main character is in the car with her partner. In what feels like a stream of consciousness these are the first things she says:

I’m thinking of ending things.

Once this thought arrives, it

stays. It sticks, it lingers, it

dominates.

There’s not much I can do about it, trust me.

It doesn’t go away.

It’s there whether I like it or not.

It’s there when I eat, when I go

to bed. It’s there when I sleep,

when I wake up.

It’s always there. Always.

I haven’t been thinking about it for long.

The idea is new.

But it feels old at the same time.

When did it start?

What if this thought

wasn’t conceived by

me,

but planted in my mind, pre-developed.

Is an unspoken idea

unoriginal? Maybe I’ve

actually known all along.

Maybe this is how it was always going to end.

Jake once said,

“Sometimes the thought is closer to the truth, to reality, than

an action. You can say anything, you can do anything, but

you can’t fake a thought.”

I think a lot of us would recognize this pattern of thought. Whenever an end arrives in whatever form possible, you start looking for the beginning of that end. I also relate to the feeling of a new thought that’s old.

What are ways to say goodbye?

Vincent

4. SPLUTTERING

Hey norms,

Let’s dive in headfirst with this one. To identify you, here is a list of the shapes you take in circus as we identified over the years

- Sexist patriarchal imagery (eg. gendered imagery and roles like the fragile woman thrown around by strong men)

- Ableist inaccessibility of circus practices and spaces (eg. repertoire of circus practices written for abled bodies)

- Heteronormative and queer -and transphobic narratives and imagery on and off stage (eg. lack of queer representation on circus stages)

- Racist imagery, exclusion of racialized people (eg. cultural appropriation of narratives, aesthetics…)

- Extractivist logics destroying and exhausting human bodies and their environments (eg. the idea of the circus body with an expiration date)

Obviously, these are norms that govern our society in general. They have long histories in capitalist colonialism, they flourish in the present and prevent other futures from happening. Because of their omnipresence, it’s important to identify how they manifest specifically within the circus field. That’s what I tried between brackets. Next to being specific about you, the governing norms, it’s important to celebrate all the artists who are doing something else. I don’t want to allow you to prevent us from seeing those who are currently creating other circuses and communities and worlds and paying the price for it. Another circus is not only possible, it exists. But how to make these alternate realities anti-fragile? How to continue them?

These axes of oppression need to be challenged in practice, at least as much as in study. That means taking these norms into account when taking everyday decisions within circus practices. If you feel that’s a drag, you’re probably, like me, not affected by (most of) these axes structuring the circus field. That means we need to change how we move, practice, curate, travel, sell, program and teach within the field. That means, and we’re talking bare minimum here: we’re not mounting any all-white festivals, we find ways of practicing circus beyond youth, we construct sustainable organs for transformative justice…

These are topics we were deeply involved with in The Circus Dialogues (continued). I will add a list of things we read below, just to share resources. The previous is not the sentence I initially wrote. My first impulse was to start a new list with impressive titles to “prove” we were working with these matters by listing some books and impressing you with the amount of literature we studied about these norms. It’s a tendency that’s as silly as it is dangerous.

Throughout the project we spoke a lot about the gap between trying to get a better understanding of these forms of oppression and actually counteracting them. We felt like all this reading, and the impossibility of not being implied in these dynamics of oppression from the places and bodies we were working from, was stopping us from acting and doing what we felt we had to do: create a practice. It was frustrating. But in hindsight, this spluttering might actually be necessary. It might be the point. Maybe it was precisely about not being able to continue as was. But then from this productive halt, where to go next? Is there even a next step?

There are some more norms that I want to address, but for which I’m hesitating to come up with a definition. At first, I thought they were somehow aesthetic norms. But no such thing as mere aesthetics, right? As an example, let’s talk about

V

E

R

T

I

C

A

L

I

T

Y

In our rigging practice, verticality is a norm we encountered throughout. It seems to be a circus convention to aim for verticality, tricks and ropes and bodies go up and down, rarely sideways. Often, rigging seems to cater for this dream of verticality. It’s made to make you go up real high, real safe. In the previous iteration of the research project, The Circus Dialogues, Sebastian Kann brought up theinspiring Inclinations: a critique of rectitude (2016) by the feminist scholar Adriana Cavarero. In this publication, Cavarero critiques the norm of rectitude and verticality as it appears in thought as it does in images, the way it is formed by supremacy of masculinity and the way that feeds our idea of subjectivity. I see this idea(l) of rectitude and the erect subject in so many circus practices. In a brilliant theoretical move, Cavarero proposes a feminist interpretation of subjectivity as inclination: the subject who is inclined toward others. From this idea of openness and inclination, we started looking for other ways of rigging that do not comply with the all-encompassing vertical aspirations, but rather generate states of inclination towards others.

Dear norms,

we see you

Vincent

Barad, Karen. “On Touching–the Inhuman that I Therefore Am.” In differences 23, no. 3 (2012): 206–223.

Bellacasa, Maria Puig de la. Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More than Human Worlds. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

Care Collective, The. The Care Manifesto: The Politics of Interdependence. London and New York: Verso, 2020.

Cavarero, Adriana. Inclinations. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2016.

Keeling, Kara. Queer Times, Black Futures. New York: NYU Press, 2019.

Sharpe, Christina. In the Wake. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016.

Wilderson, Frank B. Afropessimism. New York: WW Norton, 2020.

5. WHERE TO GO FROM HERE?

Dear way out,

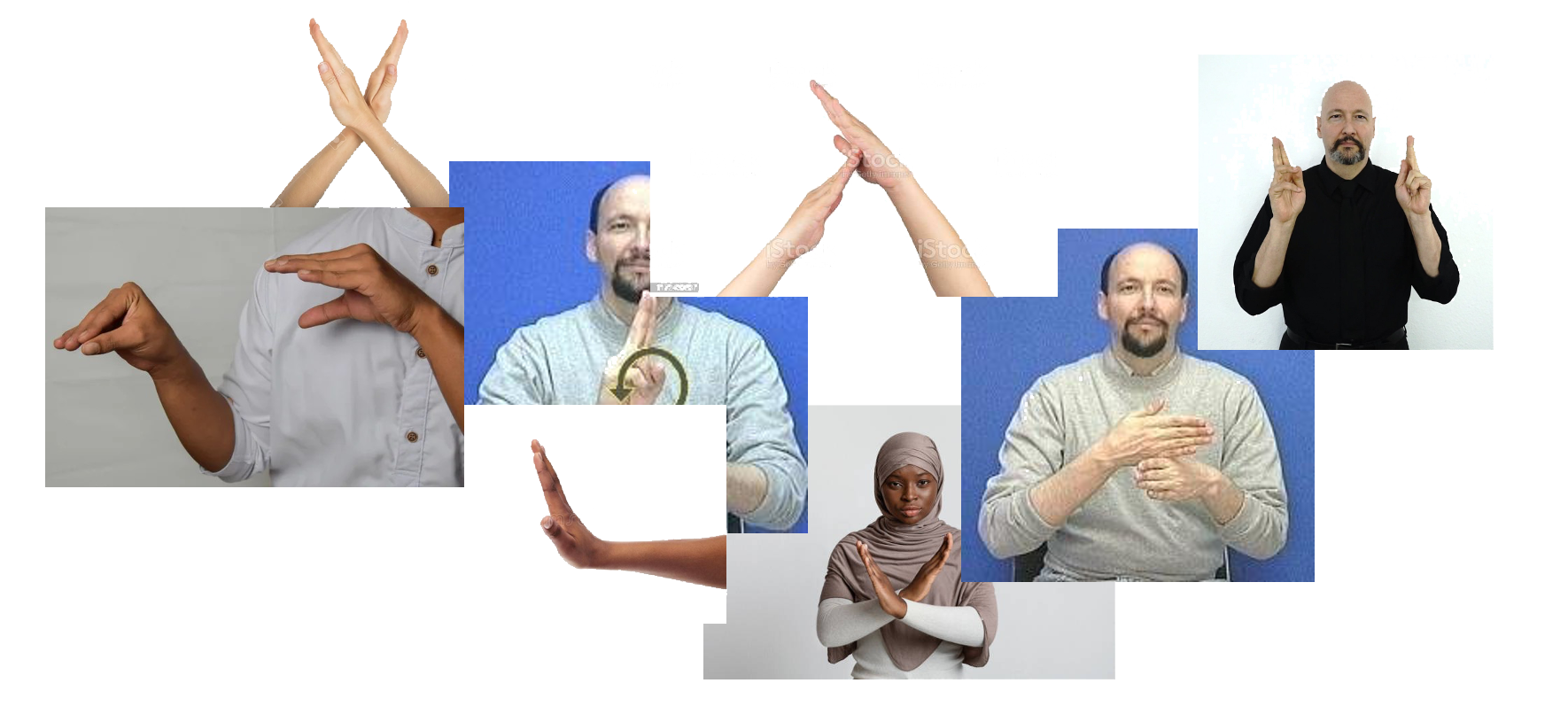

Where to go from here? I wanted to write you this letter to say that I’ve stopped looking for you. I think there is something else we can do. In The Circus Dialogues (continued), we’ve been looking for alternative ways of doing and living (together). We wanted to flee from the norms I discussed in the previous letter, we wanted for things to be better within the circus. What are the words for this fleeing?

Un

Doing

Re

Thinking

Un

Learning

Sus

Pending

I’m wondering about these ways of counteracting or avoiding norms. Here, I want to focus on the last way: ‘suspending’. I think suspension is exactly what drew me to rigging at first. Being with, in and around the practices of Elena Zanzu ((head) suspension) and Tay Lane (hair hanging), I was fascinated by the fact that the suspension of bodies seemed to bring about the suspension of fixed frames of watching and experiencing.

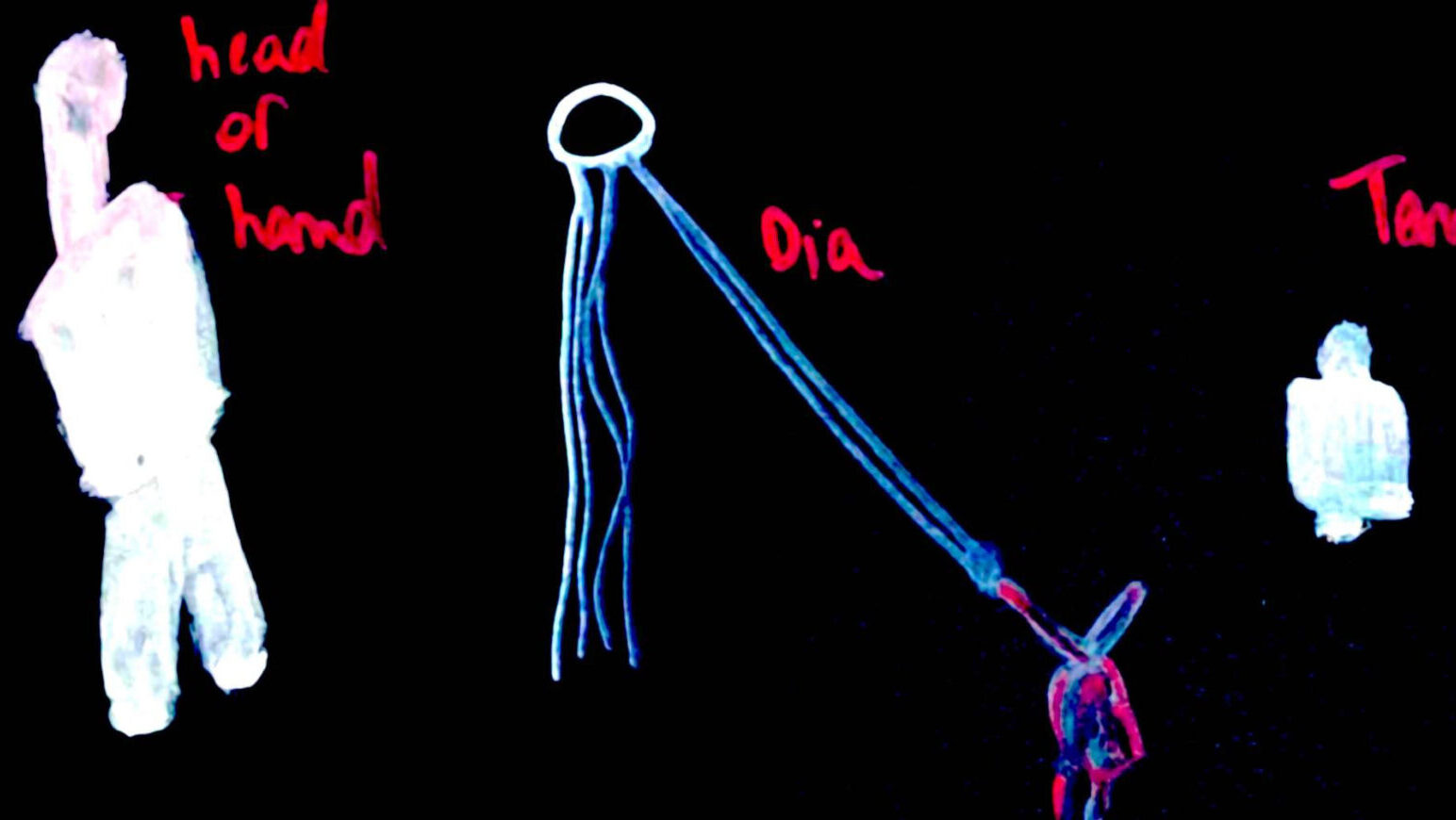

Here is a picture of Elena Zanzu, sharing his research during the first symposium hosted by The Circus Dialogues at de Zwarte Zaal of KASK School of Arts Ghent.

You see Elena carrying a participant of the symposium by the head. What you don’t see, so I’m asking you to imagine it, is a pre-negotation where the practice is explained to the participating person is explained the practice and asked for consent and given the opportunity to stop the scene whenever.

I remember this moment quite well because I could feel a suspension of the binary concepts of activity and passivity. It’s a queer experience to see someone giving themselves to a suspension, especially when that suspension will make them experience pain. There is something about this active surrendering, that laughs in the face of a binary division like active and passive.

It creates another space, a queer space in between or all-around binary frames of experience. This place feels important to me. It matters because of the violence of binary divisions and their entanglements. It matters because it could help us experiencing ourselves and our environments differently.

So, if there is no way out of the norms from the previous letter or the binary divisions, maybe there is a possibility to suspend them. To explore and create space around them and then find ways to invite people into these spaces. Maybe the way out is a space around.

I wish we could have created more of these moments in time and space: not ways out but spaces around. I hope they’re coming.

Love

Vincent

6. BEFORE YOU GO

Dear letters,

In the years past, we developed somatic warm-ups that warms up a group of people for a specific thing they will do afterwards. The warm-ups were close to (a recording of) guided meditations. We have warm-ups for reading, for dialogue, for rigging, for saying no…

Here is an excerpt from that last one, written by Bauke Lievens during a residency in Leuven

Think about the rope, imagine it spilling out of your mouth. Say out loud what you chose: yes or no. Turn your attention to the space around you. Feel the sound ripples your yes or no has created in the space around you. Has your choice made it more liquid maybe, or lighter, cleared up or hardened? Feel your feet. Think about the rope, it invites you to move. You hold out your hand in front of you, pause the invitation of the rope. Ask your hand how it feels, where is there resistance? Is it irresistible? Feel the hairs on your handle tremble. Static electricity.

I have the intuition that if we are to take preparation seriously, we need to be more specific about what we are preparing for. Going back to our practice, one of the key moments to me happened when we started identifying rigging as a form of preparation. Rigging prepares for performances or training sessions. When rigging we negotiate what we want to happen in the time coming. We negotiate what we want to make possible and what things must be made impossible. Often, riggers ban dangers like falling and injuries to the realm of the futures to be prevented. That makes a lot of sense. But what else can we pre-negotiate? What other futures can we make possible?

So, what we rig and how we rig defines what happens afterwards. Think again of verticality, if we rig differently, we can make other movements: we can incline towards who knows what. For example. Rigging differently, preparing differently, thus makes other worlds and futures possible. In general, the theatre lights go on after something is rigged. What if we focused together on the part just before? I believe the potential for change is situated there. What if we rig for care? What if we rig for refusal? What if we rig for an end? What would we need? What would it feel and smell and look and sound like? Who would need to be in and out of the space?

I want to zoom out one more time, dear letters. Look at the bigger picture, that’s what we’re there for, right? Shouldn’t get caught up in the specifics. The sensible thing to do after all this looking backwards would be to look forward for once. What comes after all this? What if we imagine these letters as rigging, and thus as preparations? What have they prepared for? This way, preparation brings us back to the beginning: endings and continuation. I hope there is enough empty space for someone to respond.

Throughout the letters, I have not once mentioned unrigging. A practice that is as important as its counterpart. Maybe that’s the task at stake now. If these letters have rigged something from an (un)finished research project, it’s our task now to unrig again. Take things apart and find new ways to put them together. To make it work again until it doesn’t. From there we see.

Goodbye, letters,

And goodbye to you too, dear reader