The Weird to the Wonderful

I don’t really call what I do circus anymore – I stopped about two years ago. I took the word off the website, took it out of all the documents, and I would say one of the reasons is really that the way circus is defined as a market doesn’t interest me anymore.

So that’s part of the definition of circus: it’s now a market, and what made circus radical in the beginning was that it left the market. It was a bad boy, it was an orphan for a long time, and that made it a very exciting form. Now it’s become like contemporary dance or it’s on its way to becoming contemporary dance.

So it’s funny because in Bauke’s writing she’s saying how she felt we needed to find ways to make circus ‘innovative, surprising, weird and disturbing’, and it really touched me because I felt that’s what I did for about 15 years – that was my goal. And I felt that with this company we were really trying to innovate and go into the marginal places and trying to provoke new ways of seeing for an audience.

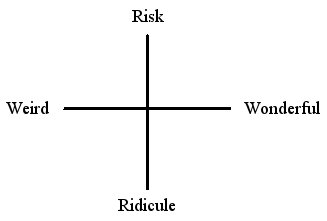

Our work was critiqued a lot for not being circus enough, and so at some point I made this compass –

– of what I thought traditional circus was and why I thought what we were doing was not contemporary circus but traditional circus, because I agree with Bauke that a lot of the definition of contemporary circus has come from virtuosity.

Right now virtuosity is the driving definition of contemporary circus and it comes from the state control of contemporary circus; in the early 70s the only virtuosic troupes were the Russians and the Chinese because they had state schools, but now we all have state schools that can produce these elite performers.

Virtuosity fits with the definition of circus as risk, but there’s more to risk than just virtuosity. For instance there’s this whole level of ridicule, of social risk – the clown’s role, but also the lowness in circus, the low art, the elephant shit on the piste. That can’t happen in theatre, it’s not allowed.

And the weird and the wonderful – there was always in circus this strangeness, it always existed. It was always bringing in whatever was innovative – the first films, whatever. Stage animals were exotic; that was why they were in the circus, and it’s why we’re so disdaining of animal acts now – because it’s no longer so exotic.

So for me for a long time this compass was my personal guide about what circus was and what I thought we were doing.

I happened to be part of the first generation of new circus artists because when I was thirteen I learned to juggle from the first generation of high level jugglers. We didn’t call ourselves circus artists at all; we did acrobatics but we called it acrobatics.

We called what we did new vaudeville.

And what’s funny is I was totally obsessed during my younger years, from sixteen through to twenty, both about what was happening in experimental theatre and about what was happening in popular theatre. And my main influence for my aesthetic was silent films and vaudeville. In vaudeville they were doing the craziest shit, really radical, and it was really connected to what was happening on the experimental theatre scene back then. So for me that was a much bigger influence than circus, and it’s quite interesting that this new vaudeville movement has basically died.

Circus is trying to be high art, but circus is a low art – and the reason it’s a battle is the institutions treat it mostly like a low art. There’s theatre and dance, classical music, and then there’s the popular arts.

I think one of the radical things in France was when circus got funding as a separate art, but it’s in France that I got a strange feeling that circus is a market when circus used to be like a contraband. Circuses used to literally smuggle goods between countries, but it was also because it was a low art. It was contraband of ideas.

Because the low arts always had much more freedom to critique the states; circus had that role, had that possibility of lampooning, making fun of the powerful.

But I personally found that the virtuosity gets in the way – it both shaped my way of imagining the work and shaped the energy I could dedicate to something because I needed to keep so much energy for the virtuosity. The cynical part of me says that technique dis-serves dramaturgy because if you spend two years working on a skill, it has to be included – it’s gonna be in the show.

Now, I’m trying to look much further back. The trad circus is not really where I want to anchor my work, and I’m trying to look at older forms of ritual and shamanism and the role they played in society. There’s a level of trance in circus that people don’t talk about so much, but it’s really similar to sufis, dervishes, voodoo. The repetition of circus artists somehow gets them into a certain state, and so there’s a personal research which can be quite spiritual but that’s linked also to what every person is looking for and why people are attracted to see circus.

I have a definition that circus is about trying to go beyond one’s physical limits, and for me that is always about trying to touch god or the cosmos or the mystery of whatever you want to call that thing up there which is outside of ourselves. So circus for me is an incredibly spiritual act, and I think that’s also why it’s really important today, why it’s necessary today.

Daniel Gulko is the artistic director of Cahin-Caha. The above is an edited transcript of the presentation he gave at the First Encounter at KASK in Ghent.